Adaptive management is an ongoing natural resources management process of planning, doing, assessing, learning and adapting, while also applying what was learned to the next iteration of the natural resources management process. Adaptive management facilitates developing and refining a conservation strategy, making efficient management decisions and using research and monitoring to assess accomplishments and inform future iterations of the conservation strategy. The goal of adaptive management is to make natural resource management more efficient and transparent, thereby making resource management agencies and organizations more credible and wide-reaching. In some instances, these goals cannot be reached by one entity implementing adaptive management alone. In those instances, strategic adaptive management is needed.

What is Adaptive Management?

Strategic conservation seeks to efficiently implement the right conservation practices in the right place in the right amount at the right time to achieve a desired set of habitat and biological conditions. Over the past century the complexity of addressing conservation challenges in the African Great Lakes Basin has increased. Resource managers must simultaneously consider multiple species, habitats, ecosystem processes, socioeconomic values, political and geographic boundaries and the other stakeholders involved when making decisions to strategically conserve the African Great Lakes ecosystem. To deal with this complexity, conservationists have developed and adopted guiding complementary management principles like ecosystem management principles like ecosystem management, landscape conservation and adaptive management to facilitate strategic conservation.

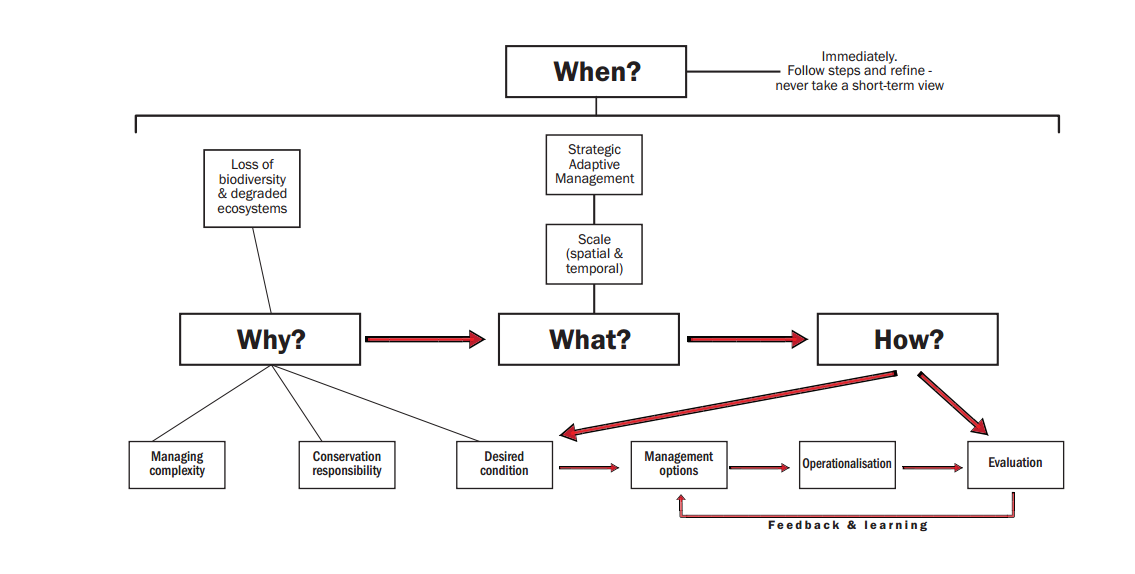

Adaptive management is an ongoing process of planning, doing, assessing, learning and adapting, while also applying what was learned to the next iteration of a management process. It is a flexible decision-making process that allows a conservation plan or project to be adjusted as the results of various actions become better understood. Put another way, adaptive management offers a way for managers to “learn while doing” and apply what they learn from each action to subsequent actions and projects. By facilitating the testing, assessing and adapting of conservation actions, adaptive management encourages innovation and experimentation, links science to decision-making and improves long-run management outcomes. There is growing scientific and practical support for applying an adaptive management approach. The figure below from the IUCN Freshwater Task Force document "Strategic adaptive management guidelines for effective conservation of freshwater ecosystems in and around protected areas of the world" provides examples of why adaptive management is necessary, what constitutes adaptive management and how it can be implemented.

Adaptive management is most likely to succeed when it is used to design projects that must be planned and developed despite uncertainty and complexity, and when managers are willing to adapt, engage stakeholders and implement all adaptive management steps. (Page iv of the United States Department of Interior’s Adaptive Management Technical Guide offers a good list of questions to consider when deciding if adaptive management is appropriate.)

Figure 1. Adaptive management: Why it is necessary, what it is and how it can be implemented. From Kingsford, R.T. and Biggs, H.C. (2012). Strategic adaptive management guidelines for effective conservation of freshwater ecosystems in and around protected areas of the world. IUCN WCPA Freshwater Taskforce, Australian Wetlands and Rivers Centre, Sydney.

Who uses Adaptive Management?

Across the conservation sector, numerous country and local governments, regional organizations and non-profits rely on adaptive management to guide their actions. The entities that implement adaptive management, however, often refer to it by different names or terms than described here. Regardless of what name and what terms are used, each entity’s process can still be labelled as adaptive management as long as it is focused on learning while doing (i.e., assessing and adapting), and also involves completing in some way the steps outlined in the next section. For a specific example of how adaptive management has been used with much success, check out the case study on the development and application of strategic adaptive management within South African National Parks.

How is Adaptive Management Implemented?

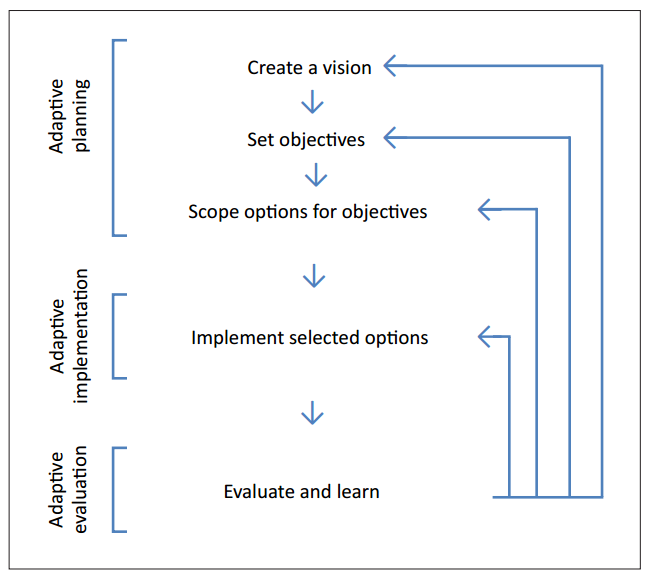

Adaptive management consists of three basic steps: Planning, Implementation and Evaluation. This framework allows natural resources managers to create a vision, set objectives, engage stakeholders to scope and review options for objectives, implement selected options, evaluate and learn and, finally, adapt as needed to achieve conservation outcomes. It also encourages stakeholder engagement and should be defined as a continuous ongoing process that changes and evolves as more information is gathered and understood.

Figure 2. Schematic of the steps in an adaptive management process. From Roux, D.J. & Foxcrof, L.C.,2011, ‘The development and application of strategic adaptive management within South African National Parks’, Koedoe 53(2), Art. #1049, 5 pages. doi:10.4102/koedoe.v53i2.1049.

The following outlines the key steps of the process, but, as noted in the previous section, the titles of these specific steps are not intended to be restrictive. Any process that involves the actions taken within each of these general steps could be considered an adaptive management process. Conservation practitioners interested in implementing adaptive management may also want to explore the numerous training materials available elsewhere, such as for the Open Standards or the IUCN Freshwater Task Force , as this article is not intended as a comprehensive instructional document.

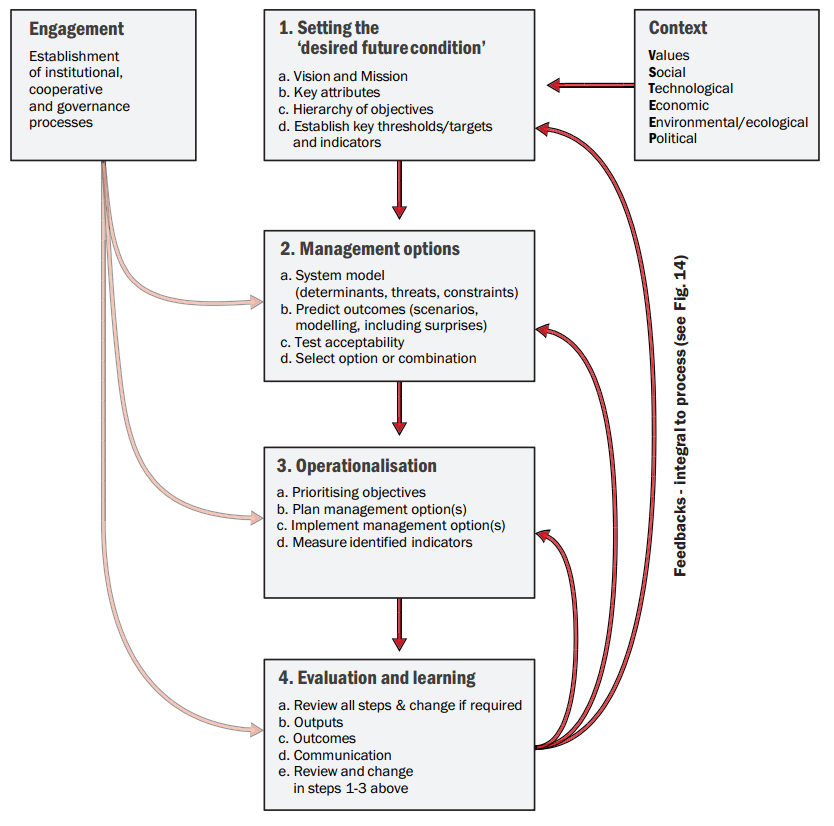

Pre-Step. Set Context

Before beginning the steps of the adaptive management process, project teams must determine the project’s social, economic, and environmental context, as this will influence the major steps (Kingsford, R.T. and Biggs, H.C. 2012). During this pre-step, the project leaders should also be identified and stakeholder engagement strategies set. It is important to begin by setting the context and defining the degree of management that is needed and that is currently in place. Beginning with this step improves the chances that stakeholders will have an accurate picture of the project and that dialogue and planning can be done with an understanding of and agreement upon the current situation. This pre-step involves developing a list of relevant values and political considerations.

Social Values

Setting context begins with a process of outlining the social values of the stakeholders. These values reflect underlying societal and organizational values that will help account for the needs of each group and will facilitate priority setting. Social values are underlain by various belief systems that should be acknowledged and considered. They may include recognition of the values necessary for management including managing for complexity; land tenure; who will be the custodian of the resource; sustainability and resilience; gender, social and intergenerational equity; learning; community empowerment and adopting a proactive approach.

Technological Values

Technological values include the availability of tools, capacity for the use of these tools and the need to apply various tools to the situation. The context surrounding what tools are required for proper management, the realistic availability of the needed tools and the capacity for applying them should all be considered before a plan is drafted. This will help identify areas where capacity needs to be increased or tools need to be developed.

Environmental and Ecological Values

For many conservation projects, planners begin with ecological values and occasionally only consider these values. Although environmental values should be established, project teams should use caution that they are developed in tandem with social and technological values.

Environmental and ecological values should include lists of important habitats and species, including rare or threatened species and species and areas of high significance. Relevant governance should also be considered. Areas of high biodiversity with poor governance may have a different priority for management than areas of moderate biodiversity with exemplary governance. All this should be noted before beginning the project plan.

Economic Values

In some situations, economic values can be developed as part of the social values discussion. Often, social values are based on the economic importance of a resource or vice versa, causing these two values to be intertwined. Protecting resources can generate economic value, or the extraction and use of resources can be seen as the only way to generate economic value. This valuation could be based on an initial subjective opinion or a detailed resource economic and social study. There may also be economic value in non-use, such as when a wetland is deemed valuable as a tourist destination.

Political and Legal Issues

There may be a list of relevant legislative, policy frameworks and overlapping mandates which are relevant to the conservation of ecosystems. Many different organizations represent different stakeholder interests and the important policies or legal contexts of each of these groups should be recorded. Social supporting processes such as protected areas, plans, mandates, governance and societal values of each stakeholder group should be identified and recorded.

Step 1. Planning

The first step in the adaptive management process is to create a plan. This plan should include objectives, strategies and a plan for assessing progress (i.e., indicators of success). External stakeholders should be engaged throughout this process. This step involves the following sub-steps:

Set the Desired Future Ecological Condition

Developing a clear idea of what to accomplish is the first part of putting together a project plan. Doing this requires planners to ask the question: Where do you want to be? A number of future-building exercises can be used to help reduce conflict by encouraging different stakeholder groups to focus on common goals. Stating the desired future condition can often reduce some of the perceived conflicts as people realize that their goals are the same or similar.

There are four sub-steps to help set the desired condition.

Derive the Vision and Mission

Vision is normally the goal in twenty to fifty years, while the mission details how to achieve this vision.

In the process of generating the vision and mission, there may be emphasis on pre-existing visions or missions. Understanding the context can provide the first step in constructing a new vision and mission. Context and values will always interact with and inform the vision or mission, and so should be understood in order to refine the vision and mission. A vision or mission often needs to be refined after moving through the other steps of the adaptive management process and should be revisited in the learning and adapting phase of each project.

Setting the vision should always be done with the involvement of stakeholders and should reflect the broad aims and responsibilities for protected areas.

Specify Key Attributes

Between five and fifteen unique and essential attributes should be identified that characterize the intrinsic biophysical, cultural, social, and economic values of the protected area (as determined in the pre-step). Often, these attributes can help stakeholders find the essence of the system and can act as powerful filters while establishing objectives.

A long list of key attributes can be counterproductive and reduce focus, making this step less effective. Look closely, as there is often high correlation and integration among attributes. Condense them into a strong, focused subset of attributes that highlight what is truly important.

Prioritize Objectives

Ultimately, the vision statement specifies the fundamental long-term objective, but it must be broken down into the relevant multiple objectives. These objectives provide a means of achieving the vision and are derived from the key attributes. Various factors must be considered when prioritizing objectives: current condition, projections for the future (including climate change), social, political and cultural objectives and realistic expectations of what can be achieved over different time frames.

The hierarchy of objectives should be clear, creating an inverted pyramid with a few general objectives at the top and several specific objectives directly relating to the protected area and desired actions at the bottom. This will lead to a series of actions that can be tracked and recorded.

A few important considerations in the development of objectives are:

- Objectives should strengthen desirable conditions and offset threats.

- Objectives should be cross-linked wherever possible to help with integration.

Establish Targets and Thresholds

Based on the key attributes, measurable targets for ecological and socio-economic action or intervention should be identified. These targets will be plants, animals, ecosystems, important areas, economic drivers, income generating activities, etc. that are important to the people and environment of the area. Essentially, targets identify what the outcomes and intervention strategies should be acting upon.

Thresholds are a critical part of the discussion on targets. These thresholds define a level or amount of a controlling variable which drives a change that causes a system to follow a trajectory toward a different ecosystem state. It is important to define thresholds for each target and avoid them, because once one of these critical thresholds is exceeded, it may become very difficult to return to the original state. Essentially, thresholds set the upper and lower limits of a variable of interest. Thresholds apply and should be identified for both ecological and socio-economic systems.

Develop Assessment and Monitoring Plan and Strategies

Adaptive management requires determining how investments and actions are leading towards the set goals at many steps and scales throughout the lifespan of the project. Doing this requires having and implementing a monitoring or assessment plan that focuses on evaluating the assumptions in a project and tracking progress towards goals and objectives. Monitoring strategies outline the related sets of goals and performance indicators and how to monitor them in a collective manner.

Indicators also need to be sensitive to change. If the indicator doesn’t tell you anything until after the damage is done, it is of less use than if evaluating monitoring is built into the process.

Develop Education and Outreach, and Training Strategies

Many projects overlook the need for education, outreach or training, but these strategies are important as they can help generate support and encourage further action in the future. A training strategy explains how to successfully implement relevant aspects of the project (e.g., trainings for field restoration workers on how to implement the shared strategies). Education and outreach strategies describe how to successfully raise awareness and convince stakeholders to support or adopt the shared objectives. Stakeholder engagement is a particularly important strategy as some projects may need to engage a variety of other stakeholders if the project has any chance of success.

Establish a Regular Cycle of Assessment and Reporting

Adaptive management is a continuous process that requires a regular cycle of assessment and reporting to inform strategic decision-making. As the assessment plan is implemented, the project managers should set a regular schedule for assessment and reporting.

Establish a Regular Cycle of Planning and Objectives Revision

Adaptive management is a continuous process that requires a regular cycle of planning that incorporates scientific advancements and lessons learned while implementing strategies or assessing projects. Each project should have a set schedule for when it will adapt.

Step 2. Implementation

This step involves developing and implementing the specific work plans for the conservation, education and outreach and training strategies formed in step one. This is the step where action begins to happen on the ground.

Step 3. Evaluate and Adapt

Adaptive management requires determining how investments and actions lead to desired objectives, at many steps and scales throughout the process, and using that information to adapt. Doing this requires developing a monitoring plan in step one and the implementing that assessment plan here in step three. This implementation requires the following:

Assess and Evaluate Progress

The monitoring plan developing in step one should be implemented here in step 3. The results found should be critically evaluated to determine what lessons have been learned and what changes may need to be made to the project. This step is often informally referred to as “tracking progress.” This evaluation and learning can be framed in a clear series of questions for the other steps in the process. It is one of the most frequently skipped actions, and usually renders the management non-adaptive.

Questions may include:

- Are the vision and mission being achieved?

- Were objectives achieved or do they need to be adjusted?

- Was monitoring adequate, cost effective and feasible?

- Were predicted outcomes correct?

- Were the outcomes acceptable?

- Were the selected actions appropriate?

Report Progress

The results found when assessing and evaluating projects, i.e., the current progress of the project, should be compiled and reported to help various decision-makers make more informed decisions on how to allocate limited resources.

Adapt Objectives and Assessment Plan

During this step, all aspects of the project should be updated to reflect the progress reported and the lessons learned. In general, adaptation involves reviewing the original project parameters, core assumptions, action plan, assessment plan, operational plan, work plan and budget and then updating or adapting these to reflect anything learned during the assessment and learn and share steps. Depending on what is learned during the assessment phase, it may also require other projects to update their plans and organizations and institutions to consider updating their policies.

Report/Share Changes and Lessons Learned

Reporting and sharing changes to priorities and objectives will help inform stakeholders about relevant updates and will continue to foster a learning environment among practitioners.

Step 4. Repeat

The above steps should be repeated continually through the life of the project.

Figure 3. Strategic Adaptive Management Framework that outlines all pre- and primary- steps of the process. From Kingsford, R.T. and Biggs, H.C. (2012). Strategic adaptive management guidelines for effective conservation of freshwater ecosystems in and around protected areas of the world. IUCN WCPA Freshwater Taskforce, Australian Wetlands and Rivers Centre, Sydney.

What is Strategic Adaptive Management?

In some instances, adaptive management cannot be successfully implemented by one entity and requires a variety of stakeholders to jointly address a problem. This generally occurs when the problem is complex, meaning that it involves a wide array of stakeholders, spans geospatial boundaries, is beyond the ability of one organization and for which the solutions are unclear.

Strategic adaptive management is the flexible decision-making process of adaptive management combined with the concept of collaboration. Strategic adaptive management involves two or more stakeholders committed to jointly implementing the adaptive management process through a collaborative process. A collaborative effort requires stakeholders to dedicate time and resources to develop collaborative processes and relationships, and to specifically put in place the necessary programs, policies and procedures that help clearly articulate their respective roles, enable effective communication and coordination of their actions and hold each other accountable to ensure they achieve their shared objectives.

Within adaptive management, collaboration can help overcome key challenges such as overlapping authority, conflicting decision-making processes and tensions between stakeholders with different issues. However, it is a challenging endeavour and is only appropriate in certain circumstances. In general, attempts to collaborate are most successful when the problem is timely and relevant parties are willing and ready to come to the table.

Stakeholder Engagement

Quality stakeholder engagement is critical to ensure cooperation, good governance and establishment of institutional processes and will inform all the steps of the adaptive management framework. Often stakeholder is most successful with the participation of a facilitator who is connected to the various groups with an interest in the project and is adept at moderating dialogues and recording ideas in an unbiased, accurate manner. It is critically important to identify champions from the community and relevant institutions who can influence the process and are well respected within their groups. This will help create buy-in and will propagate the ideas throughout the various groups, while also allowing each group to have representation. Each member of each stakeholder group must feel as though they have a voice and are being heard and respected. If one group is disregarded or their ideas not fully considered, they will likely be less willing to comply with proposed actions. There should be sufficient support and understanding within an institution on the process and enough high level detail to engage outside stakeholders. Outside stakeholders are critical to the development of a vision and high level objectives. It is ownership of affected parties that will ultimately build the capital and momentum for success.

How does African Great Lakes Inform Support Strategic Adaptive Management?

A continuous supply of data and knowledge, accompanied by up-to-date information about progress towards regional goals, increases the likelihood that strategic adaptive management will be successful. African Great Lakes Inform serves as a “first-stop” platform that complements other existing online data and information platforms. Through the site, all users can access the data, maps, tools, projects, learning resources, regional goals and theme information needed to inform their strategic adaptive management process. By facilitating the sharing and delivery of information and contextualizing and connecting these resources, African Great Lakes Inform offers the information management and delivery services needed to support issue-specific collaboratives carrying out strategic adaptive management in the African Great Lakes.