Lake Malawi/Niassa/Nyasa is the third deepest freshwater lake in the world. The basin is densely populated and has a high prevalence of water borne diseases. The lakes is home to 800 to 1000 fish species, making it the most fish species-rich lank in the world. The lake employs 56,000 fishers who harvest more than 100,000 tons of fish per year. Overall, the fishery supports the livelihoods of more than 1.6 million people. Major threats to the lake include overuse, invasive species, habitat degradation and deforestation, pollution and climate change.

Quick Facts

Bio-physical and demographic characteristics

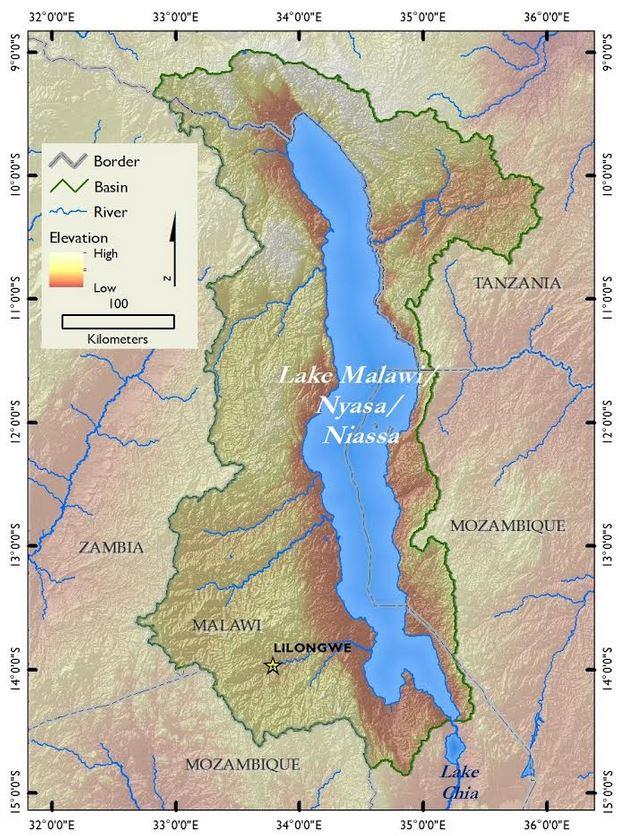

- Shared by Malawi, Tanzania, and Mozambique

- Third deepest freshwater lake in the world

- The basin is densely populated at 106 persons per km²

- Prevalence of water borne diseases such as schistosomiasis and typhoid fever

Values and investment opportunities

- Lake is home to 800-1000 fish species making it the most fish species-rich lake in the world

- Fishery is artisanal and dominated by small pelagic species

- The lake employs 56,000 fishers who harvest ~116,000 tons per year

- Fishery supports livelihoods of >1.6 million people

- Opportunity for aquaculture (especially cage fish farming, but using native species)

Ecological and economic concerns

- Threatened by overuse, invasive species, habitat degradation, pollution and climate change

- Deforestation on steep slopes and cultivation (e.g. sugar plantations), as well as uranium extraction and the planned exploitation of oil, may stimulate proliferation of water hyacinth

- Susceptible to climate change which is a threat to lake’s unique biodiversity and other ecosystem services of the lake

Governance

- Riparian countries have policies and regulations that guide development and conservation of natural resources and are parties to international treaties which bind them to establish mechanisms for managing the threats to biological diversity

- Lack of regional institution to coordinate harmonization of management interventions across the basin

- Limited funding from national governments and international groups

Potential sustainable development interventions

- Put into place a mechanism for regional cooperation in management of natural resources

- Develop mechanisms for sustainable funding

- Increase awareness through sharing of information and best practices

- Strengthen capacity of managing institutions

- Promote livelihood diversification to divert population from limited sources of livelihood

- Create an enabling environment to tap into sustainable investment opportunities

Bio-physical and demographic characteristics

Lake Malawi/Nyasa/Niassa lies in the southern end of the western arm of the East African rift valley, at 474 m above sea level. The lake was formed by volcanic activity about 2 million years ago, and the countries of Malawi/Nyasa/Niassa, Tanzania and Mozambique all border the lake. It is the ninth largest freshwater lake on Earth by surface area at 29,500 km2, and the third deepest with a maximum depth of 700 m and average depth of 264 m. Rainfall into the lake averages 39 km3/year and the lake also gains water from the Ruhuhu, Rukuru (North and South), Songwe, Dwangwa, Lilongwe, Cobue, and Bua Rivers (29 km3/year). The lake loses water through evaporation (57 km3/year) and the Shire river (12 km3/year).

The lake basin has two distinct seasons, a dry season between May and November and a wet season between December and April. Temperature ranges between 22°C and 27°C, with south easterly winds between May and September and northerly winds between November and March. A small increase in rainfall, if it is not matched by evaporation, results in flooding, while the reverse can result in the basin drying out and not delivering water to the river. The lake’s geologic history shows a major decline in lake levels at the beginning of 15th century and a possible recovery toward 1700, but persistent dry climate and low lake levels up to the mid-19th century. Lake Malawi/Nyasa/Niassa is susceptible to climate change which is a threat to lake’s unique biodiversity and other ecosystem services of the lake.

The lake region is densely populated with an average population density of 106 persons/km2. The population growth rate of 2.8 percent per year is the highest in the southern Africa region. This region is ranked among the poorest on Earth with poverty estimated at 60-65 percent, and has high incidences of diseases such as HIV/AIDS. The rate of HIV occurrence in the fishing district of Mangochi, Malawi, is 21 percent compared to the national average of 12 percent. In addition, the frequency of schistosomiasis and typhoid fever are high due to limited access to clean water. This makes the population of the basin highly vulnerable to environmental concerns, such as climate change, because of high sensitivity and lowered ability to adapt.

Values and investment opportunities

Lake Malawi/Nyassa/Niassa is home to the highest number of fish species (800-1000) of any lake in the world, with 90 percent of those species being cichlids that are only found in this lake. The lake is also an important flyway zone for migratory birds. The lake’s high biodiversity has the potential to boost tourism in the region, especially from the beautiful ‘Mbuna’ fishes. In 2014, ornamental fish trade generated US$316,255 and there is high potential to expand this trade.

Before the decline of some of the lake’s major fisheries, the lake contributed about 70 percent of dietary animal protein to the people of Malawi. Currently, the fishery is highly artisanal and dominated by small species with 80 percent of the total catches being made up of Copdochromis spp.(‘Utaka’), Engraulicypris sardella (‘Usipa’), and Lethrinops spp. (‘Chisawasawa’). These three groups alone contribute about 20 percent of dietary animal protein to Malawians. The lake employs 56,000 fishers who harvest about 116,000 tons per year, while 550,000 people are indirectly employed in the fishery value-chain. When dependents are included, the fishery supports livelihoods of >1.6 million people. Other economic benefits derived from the lake are water for irrigation, transport, and hydro-electric power generation on the Shire River that flows out of the lake.

Since 80 percent of the artisanal fisheries depend on sardines, many of which have been lost due to poor post-harvest handling, there is an opportunity for value addition within these fisheries. Other investment opportunities include aquaculture, especially cage fish farming with native species, and eco-tourism. Currently, 750 tons of fish are produced each year from 48 cages in the south-east area of the lake, and this production can be expanded with little investment. Lake Malawi is internationally known for its attractive fishes locally known as ‘Mbuna’ which in addition to those produced in aquaria, can spur the tourism industry if developed.

Ecological and economic threats

Like other African Great Lakes, Lake Malawi/Nyassa/Niassa, is currently threatened by climate change, overuse of resources, invasive species, habitat loss, and pollution. Use of destructive fishing gear and methods contributed to the decline in catches of the highly valued ‘Chambo’ fishes, and, together with habitat degradation, especially on the northern shores and parts of the southern Mozambique section of the lake, contributed to the collapse of two fish species found only in this lake, Tana Labeo (Labeo mesops) and Lake Salmon (Opsaridium microlepis). Both overuse and habitat degradation are due to the high population growth rate of 2.8 percent per year. The lake is also under threat from invasive fishes and weeds. In 2010, two highly invasive fish species, Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and Blue Spotted Tilapia (O. leucostictus) were first recorded in the Lake Malawi/Nyasa/Niassa basin. These fish pose a huge threat to the lake’s cichlid diversity since Nile Tilapia is known to replace native tilapias in most lakes in which it has been introduced. Aquatic weeds, especially water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), Salvinia molesta, and Pistia stratiotes, are, as in the case of Lake Victoria, of major concern to biodiversity. E. crassipes, was first introduced in the 1960s, but has not yet become abundant due to limited nutrients. However, the current trend of deforestation on steep slopes, agriculture in the form of sugar plantations, industry—Dwangwa Mill, the sugar industry, and ethanol—as well as Uranium mining on the western shore of the lake and planned oil extraction, may change the water quality of the lake and encourage the growth of water hyacinth.

Governance

Unlike other African Great Lakes, which have regional institutions to coordinate policies and regulations for management of shared resources, such as Lake Victoria Fisheries Organization (LVFO) and Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVBC) of Lake Victoria, the Lake Tanganyika Authority (LTA) of Lake Tanganyika, and The Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) for Lakes Edward and Albert, Lake Malawi/Nyasa/Niassa has no regional institution to coordinate management of the lake and its basin. This requires coordination and cooperation among all the stakeholders working on development and conservation of the resources of the lake and the basin. Conservation and development of the resources of Lake Malawi/Nyasa/Niassa are directly managed by the government ministries/departments/agencies of all the countries bordering the lake. Fisheries have been regulated through gillnet size limits and closed seasons, but these are still limited to small-scale fishers using beach seines. There are also regulations limiting use of non-native fishes in aquaculture, but this is currently hampered by non-native introductions already in the lake basin. There have also been efforts to promote forest and wild life conservation through education.

Each country sharing the lake basin has its own policies and regulations to guide development and management of natural resources in the basin and are parties to international treaties, which bind them to established ways of managing the threats to biological diversity.

Most funding for development and conservation of natural resources comes from national governments and external development partners and is not sustained beyond the end of the project. Development and conservation efforts have therefore been held back by limited and unsustainable funding.

Required interventions

The highest priority action for Lake Malawi/Nyassa/Niassa is to put in place a regional management plan for the three countries sharing the lake. This would then be followed by measures similar to those on Lake Victoria such as coordination of policies and regulations, networking with other regional institutions, strengthening institutional capacity, making funds available on a regular basis, sharing of information and best practices, convincing and enabling stakeholders to take action, promoting other options for livelihoods and creating an environment that enables communities to find and use existing investment opportunities.